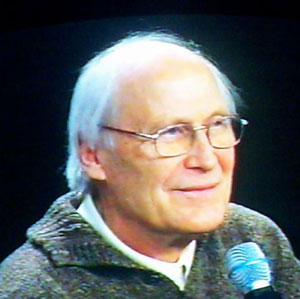

There are many streams of philosophical thought and psychological theory and practice that run into and inform Family Constellations. It was the pioneering work of a German therapist, Bert Hellinger who, over a number of years, formed the work into a separate modality using these very rich streams. He named this new way of working Family Constellations.

Rather than listing here these many influences that are integrated into Hellinger’s work, below is the complete Appendix from Love’s Hidden Symmetry. This is where Gunthard Weber & Hunter Beaumont, together with Bert Hellinger, detail the influences of Hellinger’s professional life.

Appendix

INFLUENCES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF HELLINGER’S WORK

Bert Hellinger considers his parents and his childhood home to be the first major influence on his later work. Their particular form of faith provided the entire family with an immunity against believing the distortions of National Socialism. Because of his repeated absences from the required meetings of the Hitler Youth Organization and his participation in an illegal Catholic youth organization, he was eventually classified by the Gestapo as “Suspected of Being an Enemy of the People.” His escape from the Gestapo was paradoxically made possible when he got drafted. Just 17 years old, he became a soldier and experienced the realities of combat, capture, defeat, and life in a prisoner-of-war camp in Belgium with the allies.

The second major influence was certainly his childhood wish to become a priest. At the age of 20, immediately after getting out of the prisoner-of-war camp, he entered a Catholic religious order and began the long process of the purification of body, mind, and spirit in silence, study, contemplation and meditation.

His 16 years in South Africa as a missionary to the Zulu also deeply shaped his later work. There he directed a large school, taught, and acted as parish priest simultaneously. He tells with satisfaction that 13 percent of all black Africans attending the university in South Africa at that time had been students at this one mission school. He learned the Zulu language well enough to teach and minister, but he tells amusing anecdotes about the courteous dignity of the Zulu people when he inadvertently said something rude rather than what he intended. With time, he came to feel as much at home with them as is possible for a European. The process of leaving one culture to live in another sharpened his awareness of the relativity of many cultural values.

His peculiar ability to perceive systems in relationships and his interest in the human commonalty underlying cultural diversity became apparent during those years. He saw that many Zulu rituals and customs had a structure and function similar to elements of the Catholic Mass, pointing to common human experiences, and he experimented with integrating Zulu music and rituals into the Mass. He is commited to the goodness of cultural and human variety, and to the validity of doing things in different ways. The Sacred is present everywhere.

The next major influence was his participation in an interracial, ecumenical training in group dynamics led by Anglican clergy. They had brought from the United States a form of working with groups that valued dialog, phenomenology, and individual human experience. He experienced, for the first time, a new dimension of caring for souls. He tells how one of the trainers once asked the group, “What’s more important to you, your ideals or people? Which would you sacrifice for the other?” A sleepless night followed, as the implications of the question were profound. Hellinger says, “I’m very grateful to that minister for asking that. In a sense, the question changed my life. That fundamental orientation toward people has shaped all my work since. A good question is worth a lot.”

His decision to leave the religious order after 25 years was amicable. He describes how he gradually became clear that being a priest no longer was an appropriate expression of his inner growth. With characteristic impeccability and consequent action, he gave up the life he had known so long. He returned to Germany, began a psychoanalytic training in Vienna, met his future wife, Herta, and they married soon after. They have no children.

Psychoanalysis was to be the next major influence. As with everything he did, he threw himself into his psychoanalytic training, eventually reading the complete works of Freud, and much of the other relevant literature as well. But with an equally typical love of inquiry, when his training analyst gave him a copy of Janov’s Primal Scream shortly before he completed his training, (a book the training analyst had not himself read), Hellinger immediately wanted to know more. He visited Janov in the United States, eventually completing a nine-month training with him and his former chief assistant in Los Angeles and Denver.

The psychoanalytic community in Vienna was less enthusiastic than he was about this way of including body-based experience in the therapeutic process, and he again confronted the issue of what was more important—loyalty to a group or love of truth and inquiry. Love of free inquiry won out, and a separation from psychoanalysis became unavoidable. His skill in body-based psychotherapy, however, remained an essential element in his work long after his association with Janov had ceased to be fruitful.

Several other therapeutic schools have had a major influence on his work: in addition to the phenomenological/dialogical orientation of the group dynamics from the Anglicans, the fundamental need for humans to align themselves with the forces of nature that he learned from the Zulu in South Africa, the psychoanalysis he learned in Vienna, and the body work he learned in America.

He developed an interest in Gestalt Therapy through Ruth Cohen and Hilarion Petzold and trained with them both. He met Fanita English during this period, and through her was introduced to Transactional Analysis and the work of Eric Bern. With his wife, Herta, he integrated what he had already learned of group dynamics and psychoanalysis with Gestalt Therapy, Primal Therapy, and Transactional Analysis. His work with the analysis of scripts led to the discovery that some scripts function across generations and in family relationship systems. The dynamics of identification also gradually became clear during this period. Ivan Boszormenyi-Nagy’s book Invisible Bonds and his recognition of hidden loyalties and the need for a balance between giving and taking in families also were important.

He trained in family therapy with Ruth McClendon and Leslie Kadis, where he first encountered family constellations. “I was very impressed by their work, but I couldn’t understand it. Nevertheless, I decided that I wanted to work systemically. Then I got to thinking about the work I’d already been doing and realized, ‘It’s good too. I’m not going to give that up before I really understand systemic family therapy.’ So I just kept on doing what I’d been doing. After a year, I thought about it again, and I was surprised to discover that I was working systemically.”

His reading of Jay Haley’s article about the “perverse triangle” led to the discovery of the importance of hierarchy in families. Additional work in family therapy with Thea Schonfelder followed, as did training in Milton Erickson’s Hypnotherapy and Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP). Frank Farelly’s Provocative Therapy has been an important influence, as has been the Holding Therapy developed by Irena Precop. The most important element he took from NLP was its emphasis on working with resources rather than with problems. His use of stories in therapy, of course, pays tribute to Milton Erickson. The first story he told in therapy was “Two Measures of Happiness.”

Those familiar with the full range of psychotherapy will recognize that Hellinger’s contribution is his unique integration of diverse elements. He makes no claim that he has discovered something new, but there’s no question but that he has made a new integration. He has the natural ability to throw himself into a new situation, to immerse himself in it, and when he has learned what there is to learn, to move on. Certainly, his early experiences taught him indelibly the importance and skill of listening to the authority of one’s own soul—for although it isn’t foolproof, it’s the only real protection we have against seduction by false authorities. His insistence on seeing what is as opposed to blindly accepting what we’re told, combined with the unwavering loyalty and trust in one’s own soul, is the fundamental basis upon which this work has been built.

In a sense, he’s the ultimate empiricist.

Through all of this, his philosophical companion has been Martin Heidegger, himself no stranger to the dangers of false authority—although Heidegger’s profound quest for the true words that resonate in the soul must have commonality with those sentences clients speak in the constellations heralding change for the better, signaling the renewed flow of love.

One last influence—or perhaps better, companion—must be mentioned: Hellinger’s archetypally German love of music. Yes, opera; and yes again, especially Wagner.

The above is the Appendix, in its entirety, from: Hellinger, B, Weber, G & Beaumont, H. (1998) Love’s Hidden Symmetry. Phoenix: Zeig, Tucker & Co., Inc. p 327-330.